Pediatric Care in La Paz

As of 2014, the World Bank statistics for child mortality showed that for every thousand live births, 32 children died before the age of one, in the South American country of Bolivia. This is over 5 times higher than that of the US and an astonishing 8 times higher than the mortality rate in the UK.

These statistics serve as an indicator of how this country is struggling to cope with the demand of paediatric care. Many factors contribute to the state of children’s health in Bolivia, from geographical location to high percentages of the nation living in poverty.

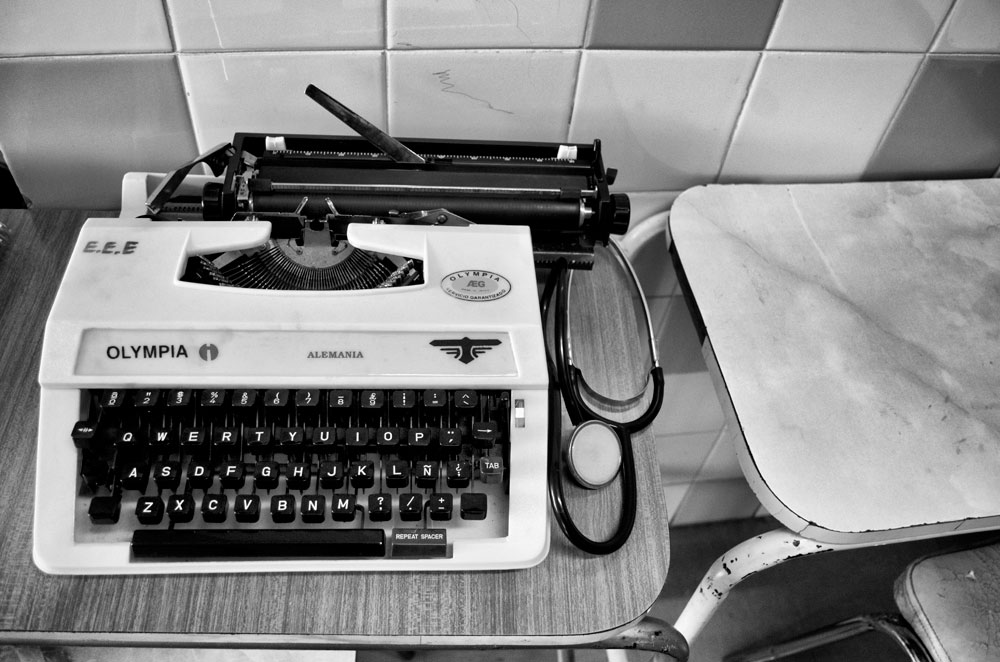

Working alongside the AAVia Foundation these images explore the issues faced daily by Bolivian children, parents and medical professionals in La Paz’s hospitals.